The best part for me, though, was helping Dr. Rosales prepare the samples. In order to be properly viewed by a scanning electron microscope, samples must be conductive--in this case, coated with a gold-palladium alloy. Samples were cut down, affixed to carbon tape, and placed in a vacuum chamber. Electricity was run through the gold-palladium, which caused it to vaporize and settle on the samples (it also glowed purple, which was cool to see).When I was smaller I had a kid's microscope, complete with slides, and I got rather good at putting together various organic and inorganic slides. So I really enjoyed putting on gloves and cutting little finicky bits of things and using tweezers to settle them just so on the dime-sized sample holders.

Actually viewing them in the microscope was something else, though. One of the samples was a fresh leaf from my creeping charlie houseplant. The leaf was fresh enough to still retain water--which made it more vulnerable to disintegration.The higher the magnification, the more focused the beam of electrons becomes. If the sample is improperly coated, or if it retains too much water, it will start to disintegrate. Which is what happened here.

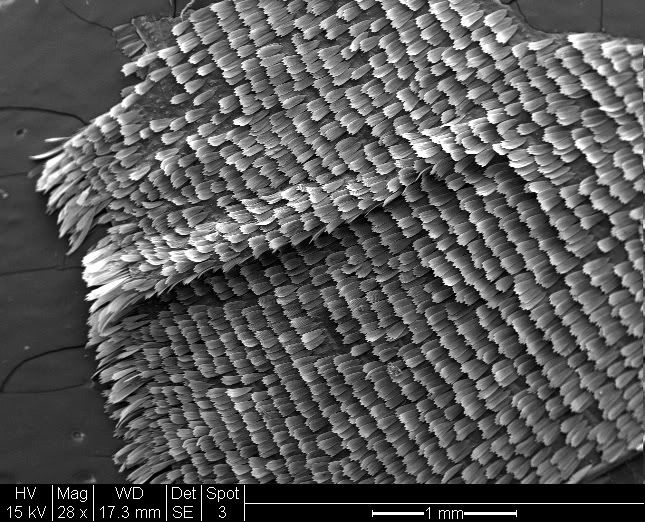

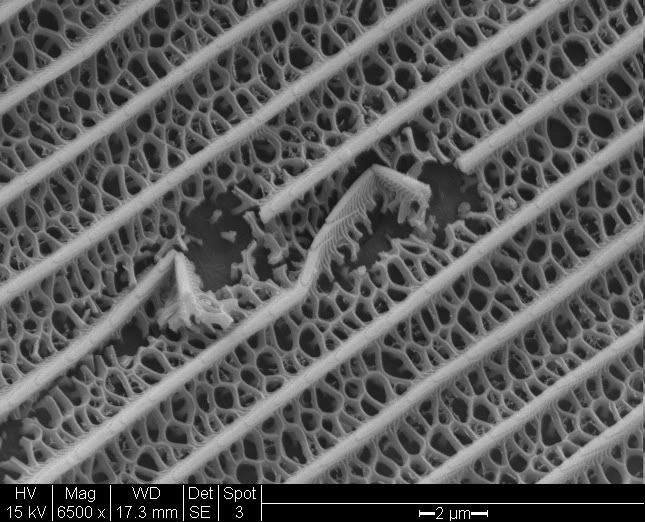

The other samples were: a housefly, a lacewing fly, the inside of a seed pod, a gingko leaf and a butterfly wing.

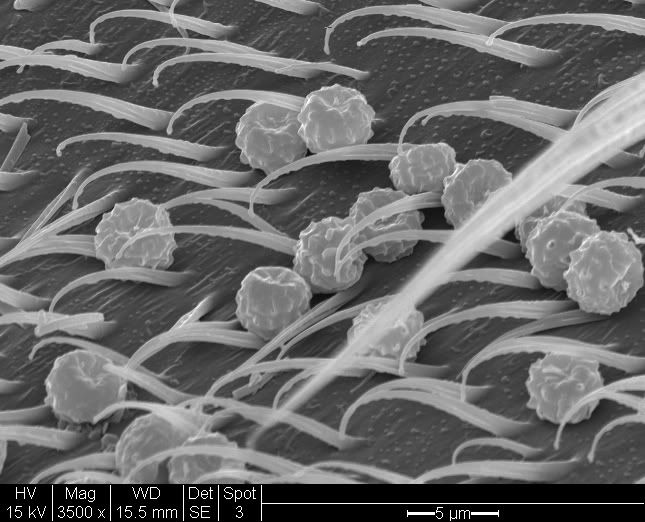

This is (presumably) pollen, caught on a fly's back.

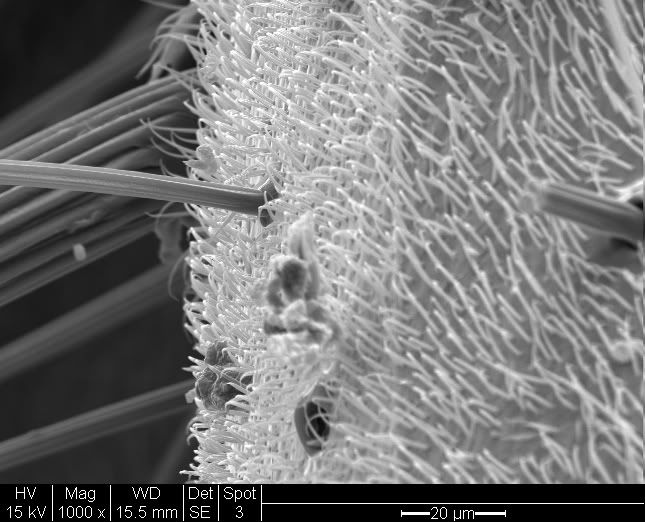

Flies are hairy, hairy bugs.

Closeup of a gingko leaf.

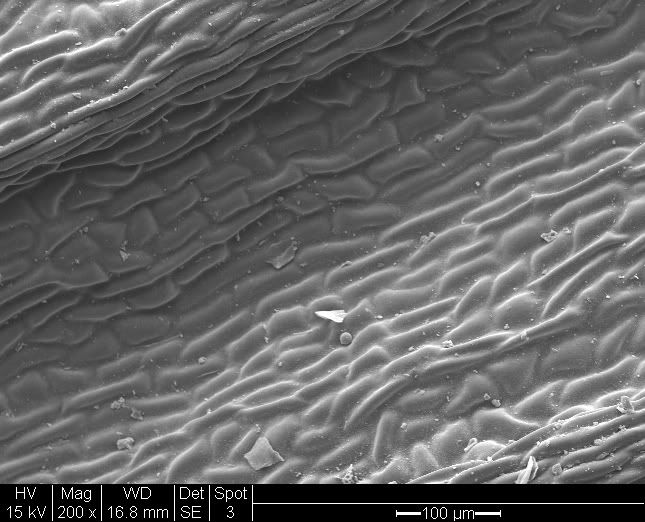

Scales of a butterfly wing.

Broken scale on a butterfly wing.

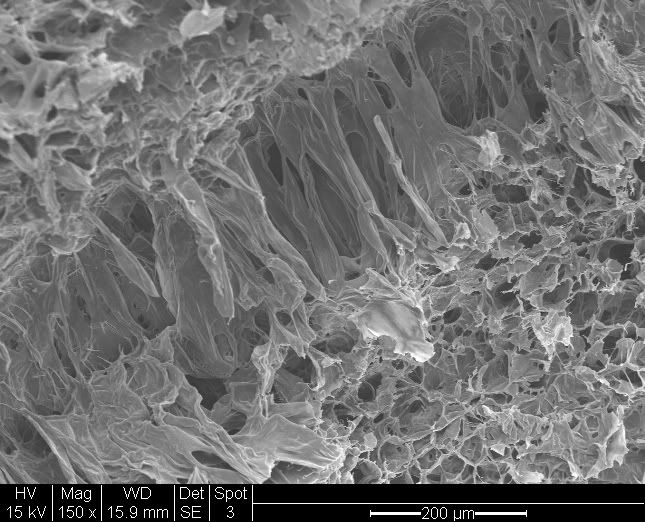

The spongy inside of a seed pod.

All the magnifications are specified on the images. These are not all the images, just the ones I liked best. All 26 can be viewed on my Photobucket account if you want to see more.

No comments:

Post a Comment